It took decades before a ban on cluster bombs came into being. And nuclear weapons still remain an enormous concern. Let’s therefore be on time, for once, in preventing machines that are able to autonomously target people, Jan Gruiters and Miriam Struyk wrote in an op-ed published on November 3rd in the Dutch daily NRC Handelsblad.

Being part of an organisation that campaigns for a ban on ‘killer robots’, it was quite a shock for us to read in NRC Handelsblad last Friday that the Dutch army should be able to buy killer robots. However, having read the full interview with former commander of the Dutch armed forces Marcel Urlings and having studied the advice to parliament that led to this interview, we thankfully concluded that things are not as bad as they were stated.

Both the commissions that wrote the advisory report, as well as their chairman Urlings, in fact turn out to agree with us: killer robots – fully autonomous weapons that are able to select and engage their targets without meaningful human control – is something that is not desirable.

The main difference of opinion between PAX, Human Rights Watch and other organisations that are united in the international Stop Killer Robots campaign on the one hand, and the commissions on the other hand, has to do the way in which this goal should be achieved. PAX believes that an international ban on the development of killer robots is urgent, necessary and the most realistic way to prevent their use. The advisory report however states that a ban is currently undesirable and would not be viable and that IHL is sufficient to protect people against the excesses of autonomous weapons. The report advocates a “responsible” approach to new technologies and urges to “closely following developments regarding artificial intelligence”. Urlings states that killer robots – and PAX’s concerns related to them – are not relevant at this time. According to the report these weapons are still decades away.

This hesitant stance is quite remarkable. Last summer 3.000 researchers in the field of artificial intelligence and robotics, together with 17.000 other scientists, called for a ban on killer robots. According to the signees, “Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology has reached a point where the deployment of such systems is — practically if not legally — feasible within years, not decades.” If so many experts are concerned and advocate for restrictions in their own field of work, there must be something going on. And there is: countries like the US, the UK, Israel, China and Russia have indicated to be interested in and are experimenting with (semi) autonomous technologies. The reluctance of the committees to take decisive steps is also remarkable because people in general are not good at judging dangerous developments correctly. From nuclear weapons to climate change, the common opinion used to be that such developments would not easily become problematic and that they would remain manageable. In the meantime we unfortunately know better.

Another argument that stands out is that a ban is hard to implement because the technology necessary for the development of killer robots will also be used in civil applications. After all, the technology that makes it possible to produce chemical weapons also knows civil applications. Yet these weapons have been banned worldwide.

Reality has shown us that the laws of war sometimes don’t offer enough protection and that strengthening of these laws is needed. For example, the ban on cluster munitions wasn’t realized until after decades of use. Trusting that all states will test weapons according to the laws of war in a realistic way is very naïve. States often interpret laws the way that fits them best. Moreover, proliferation of killer robots is a serious danger. Regulation afterwards is not sufficient, prevention is necessary.

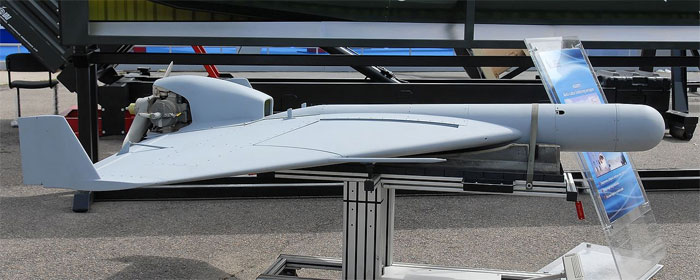

The use of armed drones shows that new technologies create new possibilities of using force and can lower the threshold for the use of force. The question should not only be what a weapon is capable of, but also what we want the technology to do for us. The increasing development towards more autonomy and reducing human control over weapon systems have consequences we cannot yet oversee. So let’s not create facts that we won’t be able to undo. Luckily the advice report contains some useful recommendations, for instance to promote the discussion on meaningful human control within the UN. Dutch former Minister of Foreign Affairs Timmermans said in this paper in 2012: “It has always been the case, in the whole of military history, that regulation lags behind the facts. First there are new weapon systems, then they are deployed, and then people start to think: within what rules does the deployment takes place and is that what we want?” We sincerely hope the Dutch government will advocate international negotiations for a preventive ban, so that “murderous machines that hunt people completely autonomously” as NRC Handelsblad stated, will remain science fiction.

Jan Gruiters, general director PAX

Miriam Struyk, program leader Killer Robots PAX